Invasive plants are a serious and costly threat to the world beyond our yards. Many of these invasives are planted in home landscapes, and indeed are the source of their spread to the wild.

What’s invasive? When we first started our habitat garden, I hadn’t heard of invasive plants, but I had heard of plants described as “invading” a garden. I learned, though, that these aggressive plants may or may not be native.

NATIVE invasive plants??

And I learned that being aggressive in a garden doesn’t mean that they’re a problem ecologically. These are what I think of as overly eager native plants, such as jewelweed. These can generally be managed.

For example, I define an area for my jewelweed and let it grow there and only there.

Non-native, invasive plants

Ironically, many non-native invasive plants — such as the burning bush in the introductory photo — cause few problems in people’s own yards. They’re often attractive and may even provide food for wildlife (though not always healthy food). There are reasons for their popularity! But they’re considered “invasive” because of the serious problems they cause in the world beyond our yards.

Some are intentionally planted

They’re the plants that escape from our yards (again, such as burning bush) and out-compete native plants in our forests, meadow, and lakes. A famous example is kudzu, but since no one in Central New York plants kudzu, it’s easier for us to judge that to be an invasive plant. What we do plant — however familiar and appealing they feel to us — can be just as bad.

Some just arrive

While I was walking around Green Lake one day (part of Green Lakes State Park), I noticed this black swallowwort and remarked that it was a shame that it has invaded such a beautiful area. My companion replied, “It’s okay as long as it stays out here.”

For a moment, I didn’t understand what she meant, but then I realized that from the perspective of a homeowner, as long as it didn’t ruin her personal landscape it wasn’t a problem.

People are used to thinking that it is our yards that are important, and anything that happens “out there” in nature is okay. We need to change how we think about this.

Infestations of invasives such as at another local state park are serious problems.

Our yards are endangering natural areas, not the other way around.

Why “invasive”?

Like most suburban homeowners, we used to have many of these invasive plants. Why not? As young homeowners, when we asked people at garden centers for suggestions or looked at landscaping books, those were the plants recommended. They’re generally readily available and quite affordable, too.

At first, it seemed odd that these could be considered invasive. We could see some native plants, like jewelweed, going hog-wild in our yard. At the same time, our supposedly invasive plants were just calmly sitting there. How could this be?

We learned that much of the invasiveness of invasive plants is invisible to the homeowner. Most of the invasion occurs in natural areas, not in our own yards.

How do they spread?

One major way this can happen is through bird droppings. Notice those berries in the top intro photo? Birds eat the berries, fly to natural areas, as they tend to do, then “plant” the seeds in their droppings, complete with its own little packet of “fertilizer.” Other ways they spread are by wind or water. At any rate, these invaders can be seen in our natural areas, and the source is primarily our yards.

Our original invasives

Some of the invasive plants we had in our yard — but mostly no longer! — were:

- burning bush (Euonymous alata)

- buddleia (aka butterfly bush) (Buddleia davidii)

- Japanese barberry (Berberis thunbergii)

- vinca aka periwinkle (Vinca minor)

- English ivy (Hedera helix)

- Bradford pear (Pyrus calleryana)

- Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica), (L. fragrantissima), (L. maackii), (L. morrowii), (L. standishii), (L. tatarica), (L. xylosteum), and (L. x bella)

- Norway maple (Acer platanoides)

- creeping bellflower (Campanula rapunculoides) – still battling this one!

- bishop’s weed aka goutweed (Aegopodium podagraria)

- roadside daylily (Hemerocallis fulva) – haven’t got it all out yet

- field bindweed (Convolvulus arvensis) – still battling this

- garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata) – we quickly remove it when we spot it

- and probably others.

And this was just in our own smallish yard!! And, sad to say, many of these were plants we purchased or that previous owners had purchased.

One of the first things we did when we started habitat gardening was to remove these invaders. Except for an occasional seedling that still pops up, it was generally easy to eradicate these invasive trees and shrubs on our smallish property. Once they were gone, they were gone.

Vines such as vinca (Vinca major) and (V. minor) (sometimes called periwinkle) and English ivy (Hedera helix) call for continual effort, but we’ve pretty much won that battle, though I see a stray sprig crop up here and there.

Here are just a few of the commonly-planted types of non-native invasives:

Official definition

An “invasive species” is a species that does not naturally occur in a specific area and whose introduction does or is likely to cause economic or environmental harm or harm to human health.

~ President’s Executive Order 13112, 1999

Be careful!

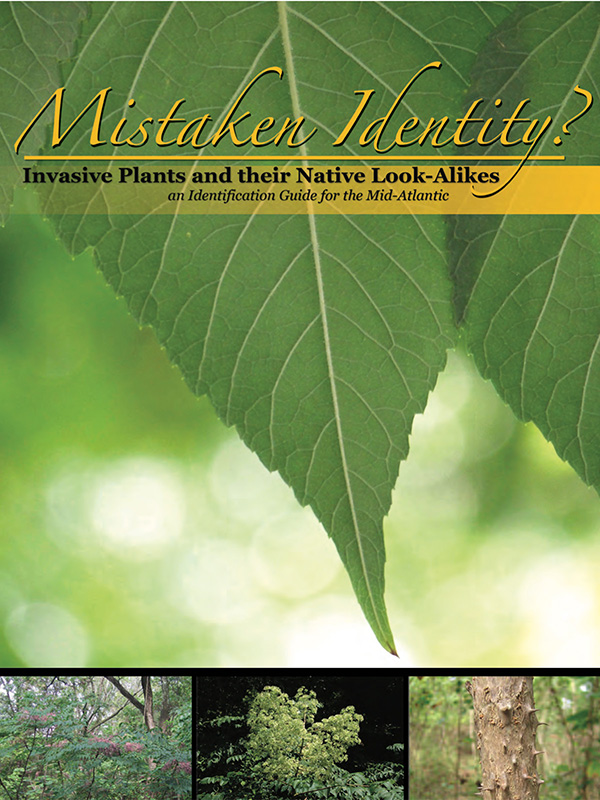

Make sure you don’t confuse invasive plants with native look-alikes! You don’t want to be eliminating a fine native plant that happens to look like an invasive plant or keeping an invasive plant that looks like a native. Here’s a free resource you can download:

NRCS and Delaware Dept. of Agriculture: Mistaken Identity? Invasive Plants and Their Native Look-alikes: An Identification Guide for the Mid-Atlantic

Resources

- Invasive plant resources:

- Invasive.org (Formerly published by NPS and US Fish & Wildlife Service.)

- Plant Invaders of Mid-Atlantic Natural Areas – Free booklet EXCELLENT! Although NYS isn’t officially in the Mid-Atlantic region, if it’s invasive in PA or NJ, it can be a problem here, too. Suggests native alternatives to invasive horticultural plants.

- Weeds gone wild: Alien plant invaders of natural areas: Factsheets for each invasive

- Invasive.org (Formerly published by NPS and US Fish & Wildlife Service.)

- Homegrown National Park:

- Helping nature take its course – Tallamy’s discussion of invasives-Excellent!

- VIDEO: What is the best way to get rid of invasive plants? – short video by Doug Tallamy

- NYS Clearinghouse for invasive species (includes CNY)

- Choose Natives:

- NYS DEC:

- NYS Prohibited and regulated invasive plants – a nice list with images of invasive plants, BUT an interesting distinction between regulated and prohibited! Please tell the wind and birds not to distribute the “regulated” plants beyond private yards!

- VIDEO: Uninvited: The Spread of Invasive Species – Excellent!

- NY Invasives:

- SUNY-ESF:

- VIDEO: Invasive species: A 2-minute video about invasive plants in people’s yards

- Penn State Extension:

- How growth form affects invasive plant management

- VIDEO: Invasive plant identification video series

- VIDEO: Sale of two popular landscape plants now banned in PA

- Sale of two popular landscape plants now banned in PA – What are they? Japanese barberry and callery pear (aka Bradford pear) (Jan. 22)

- Humane Gardener:

- New York Times:

- Audubon:

- Bee City USA:

- NY Botanical Garden:

- Don’t nab the wrong plant! Mistaken Identity: Invasive Plants and the Native Look-Alikes – an Identification Guide for the Mid-Atlantic – free to download EXCELLENT!

- National Wildlife Federation:

- Smithsonian Magazine:

- Cornell and Sea Grant:

- New York Invasive Species Information: Includes science-based information on all biological invaders of New York State—plants and all sorts of animals.

- Ontario Invasive Plants Council:

- Grow Me Instead – Beautiful Non-invasive Plants for Your Garden (For Southern Ontario, adjacent to CNY, so these would work for CNY, too.)

- Univ. of Connecticut:

- Invasive Plant List – Also invasive in CNY

Reflections

Answering the question: “What don’t we just let nature take its course?”:

In short, by eliminating the mechanisms by which mother nature used to take her course, we have, in essence, tied her hands behind her back. She no longer has the means to correct the imbalances we have created. Non-native invasive species are not superior beings that deserve to win competitive interactions with native species. They are plants and animals we humans brought to our shores simply because they were pretty, or because they were accidental hitchhikes as we moved products around the planet unlike far faster than organisms can adapt to new comers.

~ Doug Tallamy, Helping nature take its course