This section is about lepidoptera in general — not just butterflies, but also skippers and moths. I’ve discovered that many species I had previously thought of as butterflies are actually moths or skippers.

For example, a few years ago, I might have thought this pretty little creature was a butterfly, but it’s a wild indigo duskywing skipper!

(And it’s not surprising that I found this skipper since I grow its host plant: wild indigo!)

What’s the difference between butterflies, moths, and skippers?

Here are some key differences — though as always there are exceptions!

| Butterfly | Moth | Skipper | |

| Body | Thin smooth | Thick furry | |

| Antennae | Smooth with bulb or club | Thread- or frond-like | Long thin with club tapering to pointed hooks at the tip |

| Resting | Wings fold over body so undersides are visible | Wings fold down over body so wing tops are visible | Front wings held at different angle to back wings |

| Time | During day or evening | Some during day; some at night | During day |

| Larvae | Generally spin a pad of silk then hang on pad and form pupa | Generally spin a cocoon | Generally spin a pad of silk then hang on the pad and form pupa |

Unfortunately, the popular book The Very Hungry Caterpillar contains some basic inaccuracies about butterflies:

- They eat junk food.

- They eat any green leaf.

- They build a cocoon.

(Moths create cocoons, but not butterflies.)

Read more below about how we are creating REAL habitat for lepidoptera.

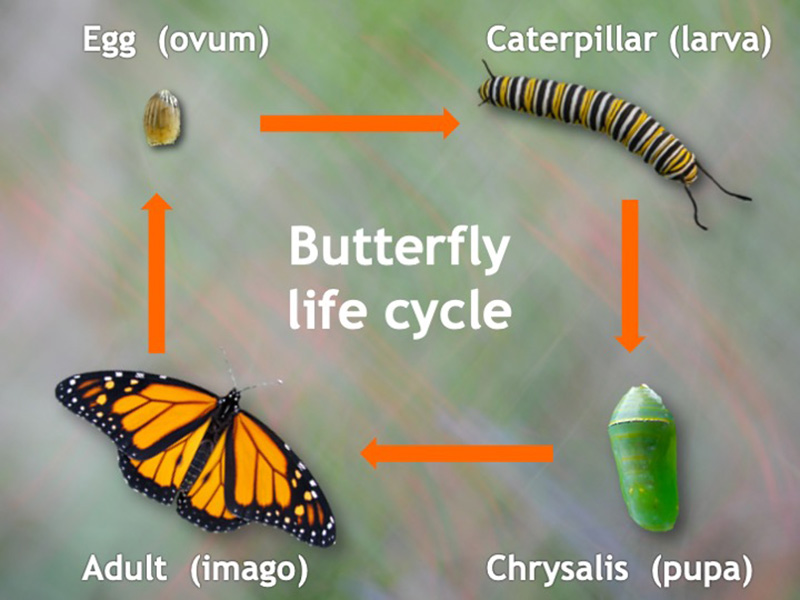

Life cycle of a butterfly

We have to provide habitat for all stages of a butterfly’s life cycle!

Here’s how we provide habitat for these insects:

- Food:

- Water

- Cover – including overwintering in various life phases

- Places to raise their young, including:

- host plants for various butterflies

- raising black swallowtails

- raising American Ladies

We have a separate section for monarchs since they have unique conservation issues and especially capture people’s interest.

Our lepidoptera

Here’s a list of all the lepidoptera (butterflies, moths, and skippers) that have visited our yard.

But we’ll never see some butterflies …

I won’t find this zebra swallowtail in my yard (though as the climate changes, who knows?)

When I first started learning about butterflies, trying to identify the species, I’d just leaf through books trying to find a match.

But then I realized that most species can be eliminated if you look at their range. No matter how much a butterfly I’m trying to identify in my yard looks somewhat like a butterfly that lives only in California, for example, it’s not likely to be that one.

This is true for selecting larval host plants, too. When I first started habitat gardening, I just looked at lists of larval host plants without considering whether butterflies that use those plants might ever visit my yard. Now I make sure the larval host plants I choose have a good chance of being used.

It’s not hard: Plants native to our region will likely be a good match for lepidoptera native to our region.

Resources

- Please don’t release butterflies at funerals, weddings, or other celebrations! Despite what butterfly “farmers” say, here’s the NABA view and those of other organizations. Many reasons to forgo the practice!

- The Xerces Society:

- BAMONA:

- Butterflies and Moths of North America collects and shares data about Lepidoptera

- Iowa State Univ.:

- BugGuide.net – a remarkable website whose volunteers help ID all kinds of “bugs”

- Monarch Joint Venture:

- Gardening for butterflies – what works for monarchs, works for other butterflies, too!

- Washington Post:

- Tufts Pollinator Initiative:

- Common butterflies of New England (good ID guide for CNY, too)

- Maine Cooperative Extension:

- PBS Nature: (If you don’t have a PBS Passport, your local library may have the DVD)

- VIDEO: Sex, Lies, and Butterflies – Fascinating info and beautiful videography!

- Mississippi State Univ.:

- Moth Photographers Group – includes photos of caterpillars, which is handy to have

- MassAudubon:

- Butterflies and Moths: Busting the myths – telling moths and butterflies apart

- Cool Green Science:

- Univ. of Wisconsin Extension:

- Winter survival strategies of common Wisconsin butterflies Excellent!

General info that applies to many types of butterflies beyond Wisconsin

- Winter survival strategies of common Wisconsin butterflies Excellent!

- Chicago Academy of Sciences Nature Museum:

- Restoring the Landscape with Native Plants:

- Caterpillars and their look-alikes – Heather Holm, author of Bees and other books

- Caterpillar Lab museum

- The Caterpillar Lab – Shows stages of the caterpillar and the adult moth or butterfly

- Humane Gardener:

- National Wildlife Federation:

- National Moth Week:

- New York Times:

Reflections

Diversity of species is a form of safety in numbers — not numbers of individuals, but numbers of ways in which each individual’s prodigious reproductive power is modulated by conflicts of interest among all the individuals with which it shares the land. The more species there are, the less likely it is that any one of them will get out of hand and — just as true — the less likely that any one of them will suffer unduly.

~ Sara Stein, Noah’s Garden: Restoring the Ecology of Our Own Back Yards, 1993, p. 13

Are our yards becoming a source or a sink for butterflies?

-Carolyn Summers, Designing Gardens with Flora of the American East